Convergence Theology: Thomism and Palamism Together

Merging Eastern Synergea and Aristotelian Metaphysics and Thomistic insight

Some wonder if it’s possible to merge Eastern Synergia with Thomistic Aristotelian Metaphysics. The answer is an unequivocal “yes, you can.” I call this Convergence Theology, and maintain that it is a necessary step to further the unfolding of divine revelation within the Church.

In the following document, I will demonstrate how this can be done. Those who cleave strongly to Thomism or Palamism may not like it, but us Catholics understand that change is constant, because divine truth is infinitely contemplated and infinitely understood, in terms of increasing understanding.

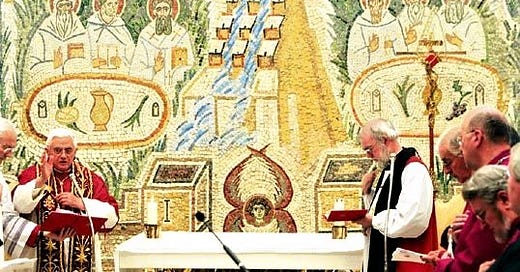

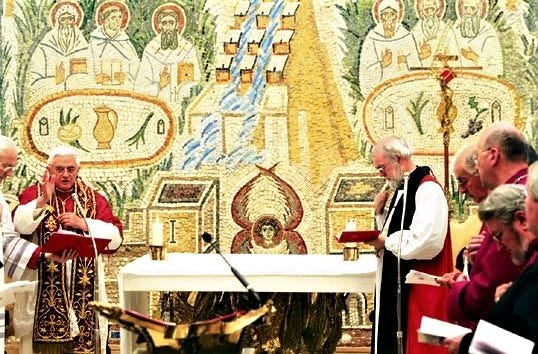

Note the presence of St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Palamas above Pope Benedict in the following picture, taken inside the Remeptoris Matter Chapel at the Vatican.

1. Grace is a Formal Cause, not an override.

In Eastern theology, grace is uncreated, not a substance imposed from outside but a participation in God’s life. Aristotelically, grace can be seen as the formal cause of a new kind of life (Divine Life), not an overriding efficient cause (efficacious grace).

The soul remains the efficient cause of its acts, but grace configures what kind of acts are possible, elevating nature. So grace is the formal cause of Divine Life.

2. Synergy is a cooperation of the Two Wills

Aristotle affirms that form and matter cooperate for an act to be realized (e.g., the sculptor and the marble). Synergy is not “God does part and man does part,” but that God’s action enables and sustains man’s free response. So the Divine Will enables and sustains the free response of a human will. It does not inject Divine Life by necessity, but elevates the soul’s capacity to freely receive or reject it.

The soul remains the efficient cause of its acts, but grace elevates the order of finality of what kind of acts are possible.

Just as form actualizes the potential in matter, so grace (form) activates the potency of the human will. But the will retains its status as self-moved (Aristotle’s kinesis), not passively moved like a stone by a rushing river.

Grace does not infuse Divine Life by sheer necessity. As even St. Thomas says, God does not will all things necessarily. Grace elevates the soul’s potency, enabling it to move freely toward a supernatural end, theosis. The will can still say “no.” The reception of grace is not pre-determined.

The actualization of Divine Life in the soul, theosis, is the effect of this synergy. The soul receives a new mode of being only after a grace-enabled motion. This safeguards both God’s primacy as First Cause, and man’s freedom as a true participant in salvation. Furthermore, God sustains and hold’s men’s decisions in existence, good or evil, making him the First Cause, but not the moral author. This is why even the decision for Divine Life is graced - it cannot exist apart from God holding it in existence. A decision against Divine Life is not graced, even though God holds it in existence because it is a creaturely act that did not require grace to make.

3. Motion V.S. Persuasion

Aristotelian movement actually includes self-motion: a thing is moved per its nature. Grace elevates and heals the will, not dragging it. Grace “penetrates” the natural faculties so that man can truly will in freedom. But this is this is metaphysical elevation, not displacement. Grace restores and empowers the will to act according to its true telos (natural end): communion with God. But the human will can, per its own nature, move against this telos.

Self-motion (per se motus) in Aristotle is real. A thing’s form, gives it its nature, which causes it to act toward its telos. Grace elevates man’s fallen faculties so this natural movement toward God becomes possible again, not automatic. It is wrong to assume hell is the natural telos of man, as we judge a thing’s true telos by what it was created for originally, not any deviations from it, such as a corrupted nature.

Divine simplicity does not require God to be the efficient cause of every volition. Instead, He is the ground of being, who sustains all acts of will in existence, but does not force their content. He holds all decisions in existence, and could do otherwise, but he does not force the content of all decisions.

God should be viewed as the Sustainer, not the Determiner. Our freedom is real, because it is rooted in being, and being is upheld by God’s generous act of sustaining creation moment by moment, including our choices. Just as God’s will is free to act according to its nature, so is ours. But because our nature is not pure love, wisdom, and justice, grace is required to choose something other than what is evil. God freely sustains a world of true secondary causes, including all our decisions.

4. Final Cause

Grace draws us toward our telos - union with God. But the means to that union (faith, works, sacraments, etc) are freely chosen, though enabled to be chosen by God. Thus, God is final cause and empowering agent, not man. When man chooses good the decision is a graced decision, which is not meritorious in and of itself, but it’s graced because it was impossible without grace. When man chooses wrong the decision was not graced, but a self-motion against grace. How this relates to Predestination is thus:

Predestination is the divine knowledge and will to bring about the final end (telos) of those who freely cooperate with grace, whose free cooperation God enables, foreknows and permits, but does not determine by necessity.

So Predestination is not arbitrary selection, nor is it sheer foresight. It is God’s eternal will to bring to glory those who are bought into the telos, and will permanently remain in it. These are the Elect.

This is not Pelagian, since the will cannot act for the good without grace. It is not determinist, since God’s grace heals and elevates the faculties but does not violate them. Nor is Predestination mere foresight of human actions, as Molinism teaches.

God predestines the order of salvation, and the individual’s inclusion in it depends on graced yet truly free participation.

5. God as Pure Act does not run counter to human freedom

God, as actus purus, gives being and sustenance and motion, but does not necessitate evil or good acts. Contingency is preserved in the creature’s reception, not in God’s causality. God’s causality is universal, but not univocal with creaturely volition. His will gives being, but does not impose determinate content on free acts.

This is akin to light shining on objects, some reflect, others absorb. But in this case, self-motion allows the object (human will) to absorb or reflect depending on what it decides. Decisions against the good are acts of madness, against reason. Humans are culpable for these freely chosen acts of madness because their reason was elevated by grace to know that they were acts of madness. As righteousness is infused in the soul, it can be said an increase of grace is infused in the soul. This explains why furthering theosis makes one more and more aware of one’s own acts of madness as sins are overcome over time.

Closing Thoughts

By allowing Aristotelian causality to inform the metaphysical structure of how grace operates, while retaining the Eastern synergistic participatory model, one obeys Pope St. John Paul’s call for a unified philosophical-theological original, new and constructive mode of thinking (Fides et Ratio 85) that both guards the integrity of revelation and engages with the theological and philosophical traditions that shape the human search for truth.

Harmonizing Palamite synergy with Thomistic metaphysics fulfills the Church’s mission to proclaim truth in a unified voice. St. Thomas, St. Palamas, and others such as St. Gregory of Narek can and must be synthesized to attain further unfolding of Divine Revelation. A refusal to integrate the Church’s broad insights and stay stubbornly pure Thomist or Palamite without consideration for other ideas will result in a stagnation of the aforementioned unfolding, and inhibit greater unity. Unity in diversity can lead to even greater unity through synthesis.

To refuse this synthesis is to paralyze the Body of Christ in a posture of suspicion rather than contemplation. But to synthesize is to love the fullness of truth, and to let the Church “breathe with both lungs.”

As an Eastern Orthodox, I have some thoughts on this.

The real question IMO is whether "sanctifying grace" can be understood to be a created accident of the soul in 'Palamism', such as whether the indwelling of the Persons is enough to account for the uncreated side but the created accident being necessary to account for the created side (along with the efficient cause being the saint himself).

Furthermore, what needs to be dealt with is in what way are the properties of the Divinity also communicated to the saint, such that the saint becomes, in perhaps a mysterious respect, literally uncreated, unoriginate, uncircumscribed etc.